A Novella from Kyanite Press’s 2019 Winter Digest

I found out that Hanson Oak, one of my favorite horror authors I follow online is contributing a story to an anthology this fall as part of a charity with Gestalt Media, I decided to update this post and re-publish, as it was one of my first (and favorite) reviews I wrote.

Here is a link to Gestalt Media’s upcoming anthology project:

The genre of myths, legends and fairy tales is one of my favorites to read. I have enjoyed all of the above since I was old enough to check out a book at the library. When I found out that Kyanite Press’s Winter Digest was going to be devoted to this genre I decided to treat myself and settle in for some long nights by the fire in the Alaska darkness, reading one tale a night and analyzing it. Before you ask, yes, I am a total nerd. When I am not writing my own stories, I am reading others.

https://kyanitepublishing.com/product/kyanitepresswinterdigest18/

I decided to begin with The Black Hen Witch, by Hanson Oak. Hanson is one of my favorite authors I follow on twitter writing in the horror/noir genre, and so I was interested to see what he would bring to the realm of the fairy tale.

SPOILER ALERT!

My original post was shorter and did not contain spoilers. This one does. If you have not yet read his story and are worried about spoilers, please stop here.

His tale is set in 1692 in Massachusetts. For those who are students of American Colonial history, something dark and sinister happened in New England that year. Something that haunts the American psyche to this day. While this craze would spread far beyond Salem like a fever, before it was done, more than 200 people would stand trial for witchcraft, and 20 would lose their lives.

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/a-brief-history-of-the-salem-witch-trials-175162489/

We can look back with the lens of history and judgement and come up with theories as to what led to such horror. Some of it was civil unrest and war in the colonies leading to refugees taxing the local economies. Some scientists speculate that ergot poisoning caused mass hallucinations and hysteria. We also know that many of the accusations were born of jealousy, greed or fear.

Knowing the time and historical setting of the story, and that the premise was an innocent young girl wrongly accused of witchcraft who is thrown together with the “real” witch of the town of Black Hen, I wondered how Hanson might play on some of the above themes. I figured he would use one of the above, along the lines of more famous books set in Puritan New England, like the Scarlet Letter, the Crucible or even the young adult story, The Witch of Black Bird Pond.

I was pleasantly surprised to be wrong on every account. He took the story’s theme in a direction I did not anticipate at all.

Disney claims in their version of “Beauty and the Beast,” that it is a “tale as old as time.” I would beg to differ. Hanson reminds us that there is a much older tale, as old as Eden. He weaves this consistently throughout his entire tale playing on traditional literary archetypes, but twisting them in unexpected ways. It is the tale of parental expectation, and how we as children either disappoint, meet, or exceed what is given to us. Do we reject our parents or accept them? Do they accept or reject us? How does this shape our choices? In particular, Hanson digs into the angst between mothers and daughters. He uses the archetypes of the mother, the crone and the maiden in particular in this tale, but often turns them on their heads.

https://www.hccfl.edu/media/724354/archetypesforliteraryanalysis.pdf

Parental Expectations and Conflict

It is something as human beings that shapes our lives. We cannot escape it, literally fed into us with our mother’s milk. It repeats itself in almost every genre, myth, legend and tale. Go to any modern psychologist, and they will analyze at length your relationship with your parents to help explain how it shapes your present relationships and life.

He starts out by creating the characters who will become the parents of the protagonist, Charlotte. They are the embodiment of the worst of the human vices: greedy, callous, cold, vain. These two people become saddled with a child who does not meet their expectations. First and foremost, Charlotte’s not the strapping boy her wealthy father wanted to carry on his legacy. Secondly, she’s sickly and ugly; the anti-thesis to her mother’s famous beauty.

On some level, the reader can’t truly blame them. Unlike in modern-day America, where most people have children (I realize there are exceptions) because they want a child to love, in the historical era in which the characters live, children are merely tools to carry on their parents legacy. Birth control (beyond the “rhythm method”) was essentially non-existent and for the most part deemed heresy. Life was harsh in the colonies, mortality was high. Life expectancy was around 35-39 years of age, That’s if you made it to adulthood at all. Roughly 35-40% died before the age of 20.

Children were used as cheap labor on farms or were shipped away from their parents at a young age to learn a trade. Obviously written about an era before the “Women’s movement,” a daughter in Colonial America that couldn’t be wed or sent off to work would be considered a horrible burden. A drain on resources.

http://faculty.weber.edu/kmackay/history%201700_colonial%20demographics.html

These two reject their daughter and treat her as sub-human. They stop short of absolute murder, but they do lock her in a damp dark room in the house, barely allowing her to thrive. They get their just desserts in the end. Her heartless father drops dead of a heart attack, then her cold, beautiful mother gets burned to death. I would love for it to have been stretched out longer, made more torturous. Kind of like Joffre in Game of Thrones, I just really wanted more suffering there. Having read some of Hanson’s other writing, I know he’s more than capable, but he was constrained by length. But that just tells you that Hanson succeeded in creating really great despicable characters (which I really enjoy reading). He did a great job creating a fitting end for both parents.

Back to our protagonist, Charlotte. She’s been shut away her whole life, however, someone is mysteriously leaving her food and whispering to her in the dark, making sure she continues to live. Charlotte manages to make it to adulthood despite her illnesses and lack of care from her parents, and seems to find love for a brief time from Christian, the Baker’s son, who she weds.

However, Christian seems to pull away from her not long after they are married to work for her father, and leaves her alone in her dark world of her room again. She’s alone, sick and lost once more.

Now at her lowest point, Charlotte is dragged out of her parents home and accused of being a witch. Her parents look on and do nothing. She calls out to Christian from the cart in which she is imprisoned, and he takes the hand of another woman and turns away.

She’s thrown in with Corta, the real “Witch of Black Hen.” This is where the tale twists again. Hanson does clever job here of spinning the maiden/crone archetypes at this point. Poor Charlotte, for most of the story, has been portrayed as almost a young crone. She’s ugly, sick, hideous, naïve. Meanwhile as soon as Charlotte strikes her bargain with Corta, the withered old hag turns into a beautiful enchanting young woman, something Charlotte has never been.

Meanwhile Hanson delves deeper into the Mother Archetype, and the Mother/Daughter hero’s quest arc in more detail with this twist in the tale. He explores much of the rage, love, bitterness and longing between mothers and daughters as Charlotte is offered a choice by the surrogate mother she never knew she had.

https://carljungdepthpsychologysite.blog/2018/03/13/the-mother-archetype/#.XBpfNvZFy74

If you haven’t guessed, the mysterious person in the story who whispered in the dark to Charlotte and left her food, caring for her when no one else did, was none other than Corta, the real Witch of Black Hen.

This is where the story comes down to morality of good and evil. Who should get to choose who does the punishing? As previously mentioned, Charlotte is offered a choice. She can choose to give her heart to the Black Hen Witch, and in exchange, receive the answers about herself and her family that have been withheld her entire life. She can exact revenge for the treatment she’s received, or she can choose kindness and love. The question remains, which does she actually choose?

But first, we must answer the question, what type of mother figure is Corta? And what is the mother figure.

The Mother Figure

Carl Jung was one of the first to document the Archetypes in literature. They have been around since the dawn of time, and they repeat themselves throughout all cultures. I have included a few websites in this essay, one on archetypes in general, and one in specific on the mother. I also included an article from Psychology Today: Mothers, Witches and the Power of Archetypes; Dale M Kuschner 2016 (see link further down), which delves deeper into the negative aspects of the Mother Figure, but also explains the reasons behind these negatives.

The Mother figure can be represented in many ways. When she is positive, she is nurturing, loving, supportive. Sometimes the embodiment of wisdom, kindness, fruitfulness. In literature she may not always be represented directly as a mother, but as a guardian or even a goddess. Athena, Greek goddess of wisdom, Mary, the mother of Christ, Ostara goddess of spring are all examples of nurturing loving archetypes.

Then she can be represented in literature in the negative: cruel, withholding, malicious, subversive. A witch, evil, destructive. Kali (Hindi culture), Pele (Polynesian), Hecate (Greek) were portrayed in such a light.

But Jung and others would argue that it is not so much that these characters are evil. They represent a side of stifled femininity that a traditional patriarchal society has suppressed and fears. They fear the powerful and untamable aspects of the feminine that they do not understand. Patriarchal societies have often created rules and laws to control the bodies and behaviors of women.

Mothers that neglect and or reject their children or act in ways that seem evil are not conforming with society’s expectations.

“…all those influences which the literature describes as being exerted on the children do not come from the mother herself, but rather from the archetype projected upon her, which gives her a mythological background and invests her with authority and numinosity.”—Carl Jung, Four Archetypes

Think about modern day America, and the extreme pressure on parents (and mothers in particular) to be perfect and give the best childhood to their children. What was considered acceptable behavior 30 years ago when I was a child would now potentially get a parent arrested for abuse, or at the very least incur the wrath of social media.

I’ll give a simple example. What is considered an acceptable age for a child to walk to school alone? My older sister and I walked by ourselves to the bus stop, by ourselves, from a very young age (I would have been six, she would have been eight). The bus stop was approximately a half mile away, across open fields of desert. We were often accompanied by our neighbors who were the same age. Meanwhile, my own mother was a “latchkey kid.” Her mom was raising her on her own with no support. She was home by herself from about the age of 7.

Now, depending on the state and laws, parents can be arrested for this.

But let’s get back into Hanson’s story and the concept of neglect and societal expectations of parenthood.

In the context and setting of Hanson’s story, while the village at large feels empathy for Charlotte’s situation, no one dares oppose the power her father has over the town by standing up for her. Meanwhile, in the context of time and place, Hanson has still done a great job of establishing Charlotte’s biological mother as merely a beautiful, empty-headed gold-digger with little to no feeling for anyone, let alone her daughter.

Yet the culture of that time would not label Charlotte’s mother as evil. It is a strange irony. She is behaving within the understood cultural boundaries of the time. There is no doubt from our modern perspective that Charlotte is being neglected and treated with unreasonable cruelty. But in the boundaries Colonial America it was perfectly acceptable. As previously stated, it is only when a person (or in particular a woman) strays beyond these bounds that they are labeled as evil, whether they really are or not.

Now we meet Corta, the Black Hen Witch:

“I was the Wind of the Woods, Spirit of the Forest, Shadow of Light, Babba Yagga, and so on. Now they call me witch”-The Black Hen Witch

Corta has been living in the woods, watching the town since its inception. Casting her magic, passing judgment, living outside the boundaries.

From Ms. Kuschner’s article in Psychology Today, I give you a quote which sums up Corta, and indeed any woman who does not conform to the societal norms of her time:

“Among the archetypes, the witch is a fascinating figure. When someone calls another “a witch,” we know exactly what they mean. The witch has powers. She is uncanny and unholy. She lives outside the borders of civilization and has been ostracized because her ways stand in opposition to accepted values, thus challenging our own impulse to conform. To not conform, especially as women, puts us at risk of being called a witch (or the rhyming word that begins with a B).”

And here we come back to parental expectations once more. Corta, unlike Charlotte’s biological mother, chose Charlotte. She has been watching her since birth. One could argue that her expectations are even higher for Charlotte. Corta wants not only wants Charlotte’s love and obedience, but she wants a companion, someone with whom she can share her power.

But as they go through the town, Corta showing Charlotte the answers she seeks and enacting revenge on those who have hurt Charlotte, Corta becomes disappointed that Charlotte doesn’t share her joy and lust in the acts of vengeance. They kill her parents, and the priest who condemned her, all despicable characters, but Charlotte’s kind heart can’t revel in their demise. Then they come to the final answer: Charlotte’s husband, Christian.

Charlotte had already suspected that he didn’t really love her. That he only married her for her father’s wealth and business connections. Her heart breaks when she sees him turn away with another more beautiful woman while she is trapped in the cart, the townspeople demanding she be burned.

Here comes both the climax in the tale and the final truths about love versus hate and good versus evil. Corta almost has Charlotte convinced that Christian never really loved her. That he wanted this other woman, and betrayed her as a witch so he could be free to remarry. Charlotte asks to hear his voice and be near him one last time regardless. Constrained by their bargain, Corta is forced to comply.

This is where we find that Christian loved Charlotte all along. The other woman is his cousin, skilled in healing whom he brought from Boston to try to save Charlotte, but was too late to save her from the accusation of witchcraft.

But who actually accused Charlotte of witchcraft?

The accuser was none other than Corta herself. When she was caught, she accused Charlotte because she claims she didn’t think Charlotte could survive without her.

Now as this is a novella and Hanson didn’t have much space here to delve into the deeper background and psyche of Corta, this portion is rather open ended.

What if Charlotte had never been accused and Christian had been able to save her? Corta would have then lost her “adopted” daughter to her husband, possibly forever, and Corta would have been burned as a witch with no way to regenerate.

If Christian’s cousin had not been able to save Charlotte, and she had died a mere mortal death, Corta still loses Charlotte.

It is both her own selfish love of Charlotte and her image of being the lone savior to Charlotte that drives Corta motives and desires. She wants to be the only love of Charlotte’s life, with no competition. She wants to sever any connection to the physical world that Charlotte has and bind her only to herself. When Charlotte discovers the truth and lashes out at Corta, Corta becomes furious. She begins to reject Charlotte.

This is also where we feel Corta’s true depth and loneliness and realize there is more to Corta’s longing for Charlotte than we know. Charlotte recognizes the true love that Corta has for her (no matter how selfish it may be).

Here is another interesting twist in the tale. In our modern society there tends to be a focus on romantic/erotic love, to the detriment of all others. The ancient Greeks actually defined 7 different types of love. Psychology Today’s article on the subject describes these in detail, written by Neel Burton, MD: These are the Seven Types of Love, June 25, 2016

https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/hide-and-seek/201606/these-are-the-7-types-love

At end of the tale, Charlotte chooses to go with Corta, begging her true mother to love her and forgive her. The focus becomes the love between mother and daughter. This is defined as “Storge,” in Greek terms. It is related to “Phillia.”

Though that the same time, Hanson acknowledges Charlotte’s continued love for Christian. But it would not be deemed what our society would consider Romantic or Erotic love (“Eros” in Greek Culture). Their love is also more along the lines of “Storge” and “Philia” as defined by the Greek model in the referenced article.

Charlotte’s final request before relinquishing her heart to her true mother is that while the town be wiped from existence, Christian is to be spared. She loves Christian still, but is willing to let go and move on with Corta. The only remnant of the town that exists is the ancient oak tree that once stood at the center, that holds her heart, evergreen.

I really enjoyed this novella. This could easily have been turned into a full-length novel. Maybe Hanson could be convinced to do a novella on Corta, so that we can understand a little more of her origins, desires and motives. Where did she come from? What brought her to New England? Why did she choose Charlotte?

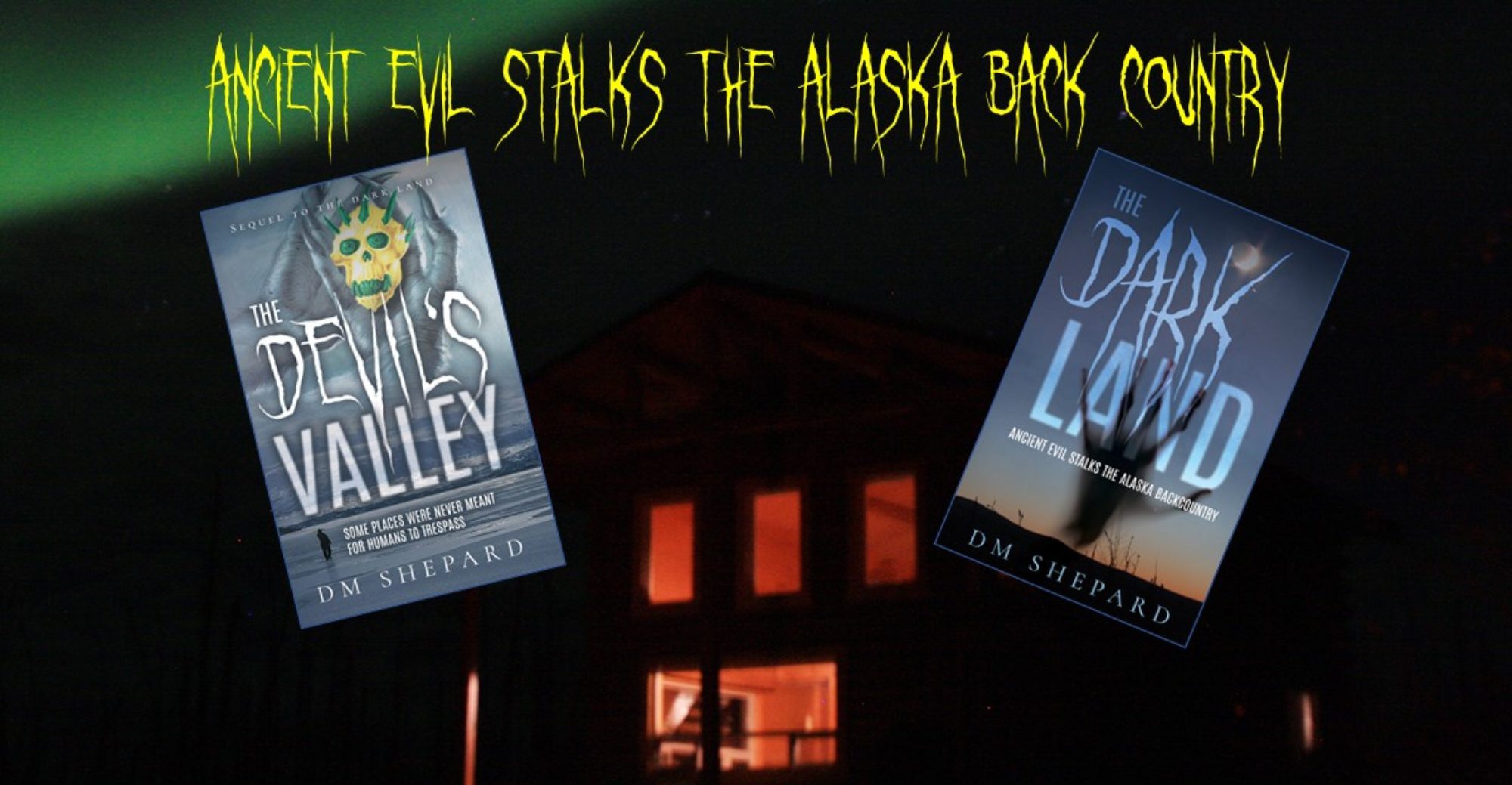

Thanks for sticking with me. If you liked my review, please follow me and check out my other posts. I have been doing a series of posts on the gold rush and the Alaska interior in the 1890’s. My next book review will be of DK Marie’s Fairy Tale Lies.

Most excellent review and analysis!! Loved every word, every insight.

Thanks Danielle! Very sweet of you.